1 Correlation is a statistical measure of how two investments move in relation to each other. A correlation of 1.0 indicates the investments have historically moved in the same direction; a correlation of -1.0 means the investments have historically moved in opposite directions; and a correlation of 0 indicates no historical relationship in the movement of the investments.

2 Statista, total companies worldwide, 2023.

3 OECD, 2022/2019.

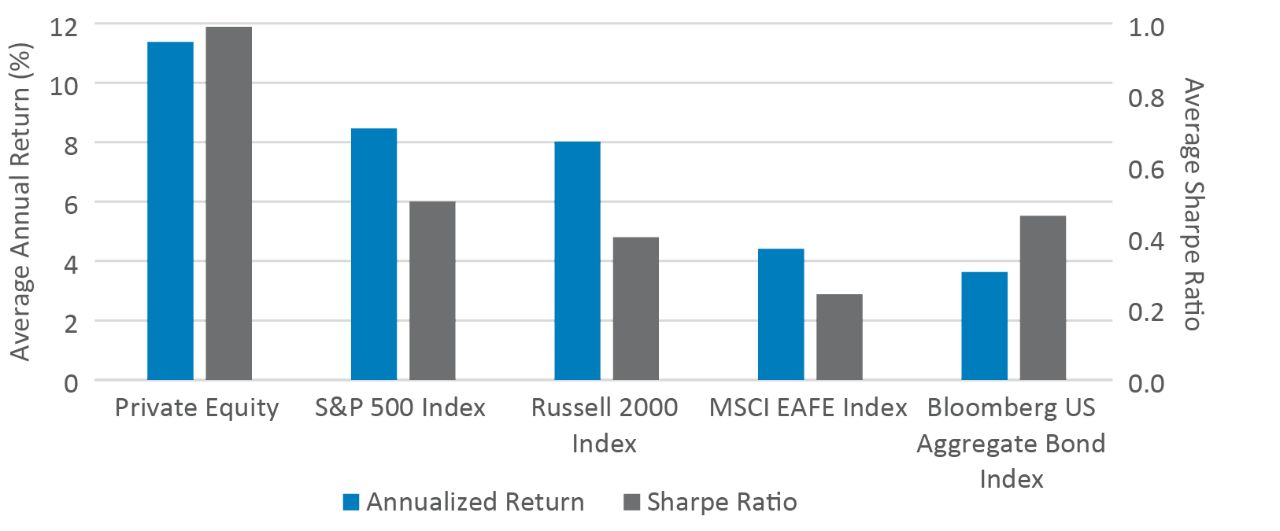

4 The illiquidity/complexity premium refers to the additional return investors may earn for taking on the risks associated with investing in assets that are harder to buy or sell quickly (illiquid) and more difficult to understand or manage (complex). This premium compensates for challenges like limited market access, less transparency, and greater operational demands.

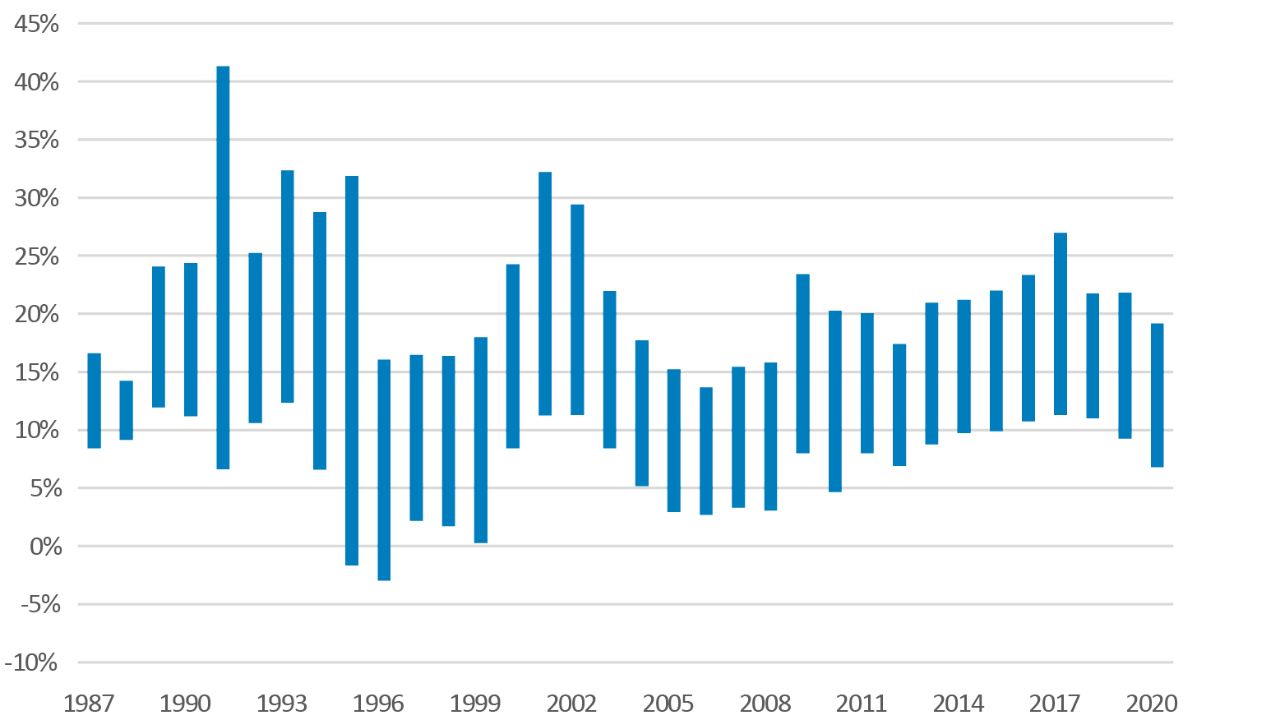

5 Dispersion refers to the wide range of returns among private equity managers—meaning some perform exceptionally well, while others may significantly underperform.

6 Lock-up periods are the time investors must commit their money to a fund without being able to withdraw it

7 Capital calls are when a private-equity fund asks investors to send in part of the money they committed, usually as new investments arise. Instead of paying everything upfront, investors fund these calls over time and need cash ready when asked.

8 Tender offers are subject to the approval of a fund’s Board of Trustees. Shareholders generally will not have the right to require a fund to repurchase shares. A 2% early repurchase fee is often imposed on tendered shares held less than one year.

Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index is composed of securities that cover the US investment-grade fixed-rate bond market, with index components for government and corporate securities, mortgage pass-through securities, and asset-backed securities.

MSCI EAFE Index is a free float-adjusted capitalization index that is designed to measure developed-market equity performance and excludes the US and Canada.

Preqin Private Equity Index is a benchmark that tracks the net performance of global private equity funds using real cash flow data, offering a clear view of how the asset class performs over time. It reflects the actual returns received by investors after fees.

Russell 2000 Index measures the performance of the small-cap segment of the US equity universe.

S&P 500 Index is a market capitalization-weighted price index composed of 500 widely held common stocks.

Important Risks: Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. • Private equity investments involve a high degree of business and financial risk that can result in substantial losses. The valuation of private equity investments is complex and is typically based on fair value. • Illiquid and restricted securities may be difficult to dispose of at a fair price. A particular investment may become illiquid, making it difficult to sell that investment at an advantageous time or price. • Foreign investments may be more volatile and less liquid than US investments and are subject to the risk of currency fluctuations and adverse political, economic, and regulatory developments.

Diversification does not eliminate the risk of experiencing investment losses.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and should not be construed as investment advice. They are based on available information and are subject to change without notice. Portfolio positioning is at the discretion of the individual portfolio management teams; individual portfolio management teams, and different fund sub-advisers, may hold different views and may make different decisions for different clients or portfolios. This material and/or its contents are current as of the time of writing and may not be reproduced or distributed in whole or in part, for any purpose, without the express written consent of Hartford Funds.